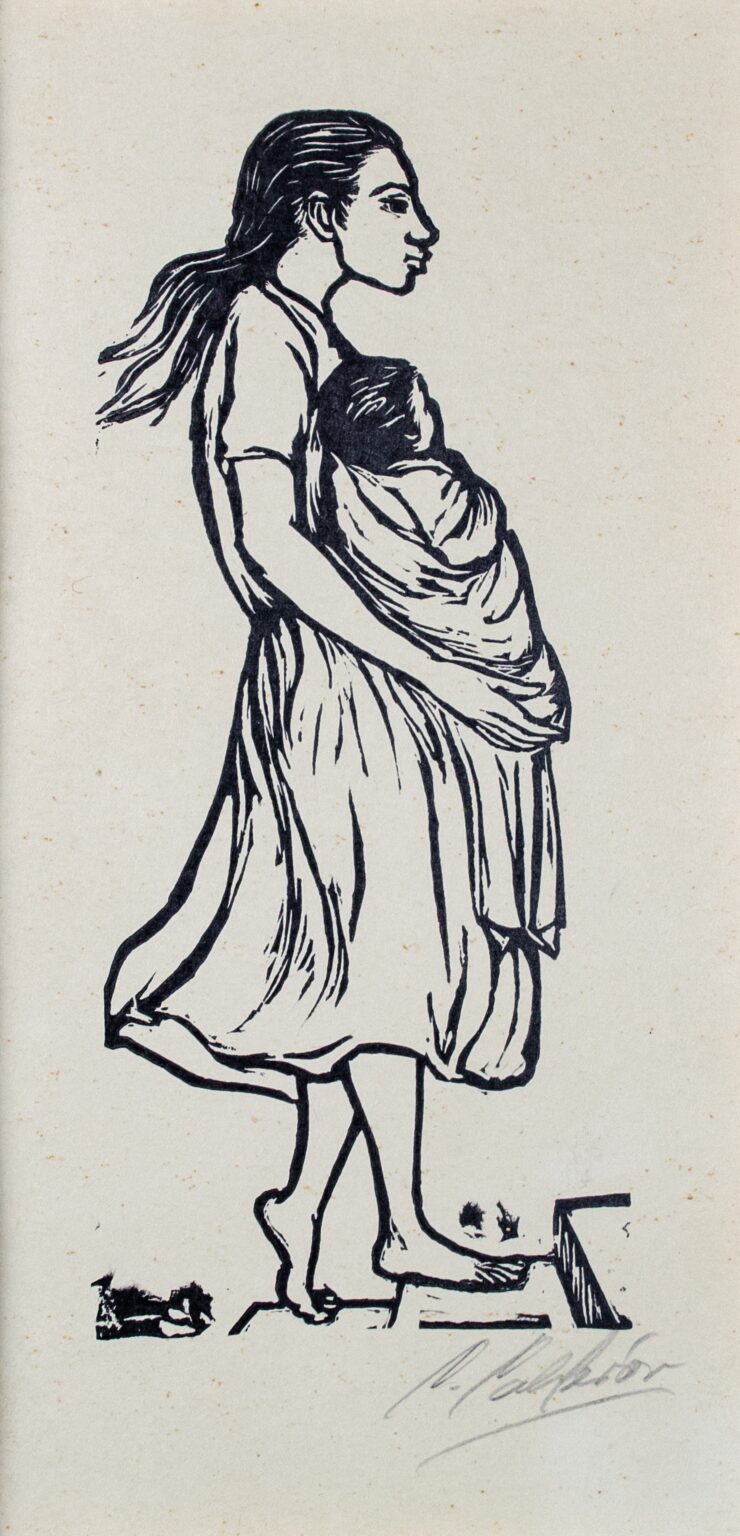

Artist: Celia Calderon

Artist Nationality: 1921 - 1969

Artist Dates: Mexican

Title: La Escalera

Date: 20th century

Condition: Good condition overall, tiny foxing spots apparent

Medium: Linocut

Dimensions: 10 x 5 1/2 in.; mat: 12 1/2 x 6 in.

Estimated Value: $500

Signature/Markings: Signed in pencil lower right, label verso

The following excerpt is taken from Dina Comisarenco Mirkin, "A Collective Roar from the Taller de Gráfica Popular:Mariana Yampolsky, Elizabeth Catlett, Fanny Rabel and Celia Calderón," Artelogie [En ligne], 17 | 2021:

Celia Calderón was born in 1921, along with the muralist movement. Although little is known of the artist’s early years, we know that between 1942 and 1944, in the midst of World War II (1939-1945), young Calderón studied at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas (ENAP), where she took classes with distinguished professors such as Julio Castellanos (1905-1947).

After winning a drawing contest, Calderón was offered a scholarship from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México to continue her formation at the Escuela de Artes del Libro. Along with Francisco Díaz de León (1897-1975), Calderón took printmaking classes, a medium in which she would eventually excel.

Along with some of her colleagues, the artist founded the Sociedad para el Impulso de las Artes Plásticas. Then, in 1947 she was invited to join the Sociedad Mexicana de Grabadores (SMG), an organization that contributed enormously to the valorization of printmaking in Mexican art, as it had the participation of important figures. Calderón was also, from 1949, a founding member of the Salón de la Plástica Mexicana, an outstanding instance in Mexican art that would award her the Premio de Invierno in 1955.

Some years prior, in 1950, Calderón had obtained a scholarship to study in London’s Slade School of Fine Arts, financed by the INBAL and the British Institute. In that time, Calderón was in charge of the Taller’s exhibits, a job she retained until 1959. Then, between 1963 and 1965, the artist was the collective’s director.

Even within the Taller’s collective works, Calderón manifested for the most part a marked interest for women’s portraits, be it anonymous or historical figures. Thus, for example, when in 1955 Elizabeth Catlett invited her Taller cohorts to provide illustrations for an article about the “History of Negroes in North America,” to which we referred to above, she opted for portraying Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862-1931), the journalist, teacher and early leader of the rights of African-Americans who dedicated her life to fight against prejudice and violence, as well as for the equality of African-Americans, especially women.

Taking into consideration the general context of women’s organizations of that era, mainly of the Unión Nacional de Mujeres Mexicanas, the feminine branch of the Partido Comunista, with whom some artists were connected, the themes of the female TGP printmakers often coincided with their revindications of maternity, childhood happiness, and a defense of youth, maintaining a pattern of domesticity that was supposed to correspond to the feminine sphere.

Consequently with these interests, Calderón made numerous maternities. The earliest ones were done with very sculptural forms, à la her teacher Castellanos, portraying indigenous women as was characteristic of the Taller, sometimes emphasizing their poverty and vulnerability, as well as their sacrifice and pain due to overseeing their families’ care. Calderón used other opportunities to emphasize maternal happiness, sometimes even, throughout the titles and the formal treatment of her pieces, imbuing them with the sacredness of Christian iconography. The artist even created psychological portraits not only of one mother, but the feeling of worry, personal realization or contemporary problems such as the premature maternity of so many women or the role of mothers that many girls must play due to the harsh life conditions of their own mothers.

In Calderón’s overall work, it’s striking that instead of emphasizing women’s conditions of subordination and marginalization, many of her pieces highlight not only the role of women in normally ignored areas such as education or reading, but what is represented is the camaraderie and sorority among women that occurs in the workplace (fig. 4). Calderón’s work also highlighted many other situations that unites women intergenerationally, like the birth of a baby, as well as the cathartic dialogue that rises naturally in an intimate moment of rest and confidence when women cry and laugh together, or the moment of gossip, like in her drawing titled “comadreando,” a term used commonly to refer to the supposed penchant women have for talking excessively, for murmuring and for gossiping. But more than the prejudices of said characterization, behind it all is a reference to the solidarity, complicity and fellowship of women.

Calderón, by concentrating in the representation of activities carried out daily by women that are interpreted from their own closeness to the fight for women’s rights as well as from Calderón’s own experience as a woman in an eminently patriarchal society, avoided falling into the trap of the rigid definitions of the feminine gender’s identities. Thus, instead of reiterating feminine solitude, such as happens in so much Mexican art of the 20th century, she set out, on the contrary, to dismantle the macho myth that claims there is no friendship between women.

Provenance:

Private New York Collection

Exhibition History:

Publication History: